Last week I attended the brilliant Symposium Mammographicum. It was my first attendance and I wasn’t disappointed. It somehow managed to appeal to the wide ranging audience of practitioners from all four tiers, researchers, and radiologists. The speakers came from all these groups. The poster section was superb and to top it all, I was delighted to find that my own presentation on the WoMMen breast screening hub was highly commended.

For me, though, most anticipated was the session about the benefits and harms of breast screening delivered by a panel of world-renowned experts in the field. I was hungry for information to put onto the WoMMeN hub. I therefore tried to listen to the speakers as a member of the public would; what information would I find useful to help me understand breast screening?

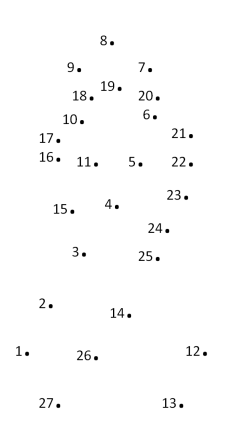

Individually, each presentation was expertly researched, prepared and delivered. I was enthralled. But this session also left me frustrated. Across the four talks there seemed to be some obvious solutions to the problems they had identified. However, as is often the way at conference, there was little opportunity to join the dots: I left with an urge to join do some dot-joining of my own.

Dot 1: risks versus benefits

Professor Stephen Duffy provided an excellent comparison and summary of a number of high profile breast screening evaluations. Each of the evaluations aimed to review risks versus benefits in an attempt to answer the million dollar question: is breast screening effective? Each had used similar types of data yet each had arrived at different conclusions. These contradictions had always confused me. What Prof Duffy did was to unpick the methodologies to demonstrate that the differences in findings were not as extreme as first appeared. The balance, concluded Prof Duffy, appears to lie in favour of screening.

Fabulous, now I understood and this will help inform my own personal breast screening decisions. But I wonder about the breast screening population at large? Who tells them? They remain confused.

Dot 2: patient information

Dot 2: patient information

Dr Kate Gower Thomas demonstrated that breast screening up-take started to decline around the early naughties. She suggested this might be because of poor information, showing women prefer word-of-mouth experiences of friends and relatives and on-line resources to evidence-based Breast Screening Programme information leaflets. Dr Gower Thomas argued these sources can potentially misinform, e.g., sensationalised accounts of breast evaluation reports by the media. Social Media (SoMe), might also be a contributory factor with women sharing negative stories of the harms and risks of screening.

Excellent; 2 dots were coalescing in my mind. If women are as confused as I had been about the contradictory reports and yet they had no eminent professor to help them make sense of this information it is possible that Dr Gower Thomas was right. Women need someone like Prof Duffy to put it in lay terms and post on SoMe. We could use SoMe as a power for good!

Dot 3: informed choice

Dot 3: informed choice

Regardless of how the risks are explained though, a woman’s decision to attend breast screening depends on her attitude towards risks and benefits. This was the focus of Dr Ruth Jepson’s talk. Her message was that in this era of informed choice the aim of screening programme information should not be to increase uptake. Instead we should aim to provide high quality information and respect a woman’s choice, whatever that may be. Balanced information means highlighting risks and benefits in equal measure, something that has been done in the latest version of the BSP “Helping you decide” information leaflet. The problem is, as Dr Gower Thomas had shown (dot 2 starting to join up with dot 3?) women don’t read information leaflets; they go to on-line resources where the balance of information appears to favour risk.

So, could this emphasis on risk be a reason for decline in uptake? Someone asked the panel a similar question: if informed choice is the aim, should we do away with uptake figures? A few dots were being joined but swiftly erased when it was explained that a specific uptake target is necessary in order to demonstrate ‘population advantage of benefit versus risk’. Conflating population-based medicine with individual-based care and patient choice is not helpful for clarifying aims because it appears interventions to increase uptake (playing up benefits) can be at odds with those which encourage choice (identifying risks). From the audience’s response this has also led to confusion in the workforce about whether their role is to promote breast screening or not.

Dot 4: AHPs and public health

Dot 4: AHPs and public health

Linda Hindle spoke about the role of AHPs in public health. The audience was in agreement; this is a role for us. This was encouraging and reflects the fact that mammographers work in a screening programme which uses ionising radiation; these are explicit items within the ‘Health Protection’ domain (one of four domains in Public Health England’s definition of public health). Mammographers could be instrumental in communicating information about breast screening to the public.

But Linda’s emphasis was on the other domains such as Health Improvement: obesity, smoking, fitness and exercise. Her message was that mammographers, like other AHPs, should be Making Every Contact Count : i.e. talk about these things during your encounter with screening patients. A delegate asked wryly which of these she should key into in her 5 minute client encounter as she wouldn’t have time to cover them all. Couldn’t mammographers be doing public health activity related to breast screening to address some of the issues in dots 1, 2 & 3?

So four really inspirational dots in their own right but which cry out to be joined – here’s my attempt:

- Women need balanced and comprehensible information to make informed choice, and need to be able to identify misinformation.

- Misinformation and negative stories have the potential to impact on breast screening up-take.

- For informed choice, risk information needs to be given but in a non-sensationalised way.

- Women prefer word of mouth and on-line sources, including SoMe, to written leaflets.

- Online sources and SoMe networks can create and perpetuate misinformation and negative stories of risk in a sensationalised way.

- Health professionals and researchers have the knowledge and skills to distinguish information from misinformation.

- SoMe is a powerful and dynamic form of communication that won’t go away. If this is where women go to share information we need to go there too.

- Mammographers, like all AHPs, are encouraged to embrace a public health role.

- The power of the internet and SoMe networks could be used to engage practitioners in this emerging public health role to direct women toward balanced and high quality current information.

- Researchers should be enabled to write summaries of their work for the general public and share using SoMe.

If we don’t find a way to share research findings with the public in a format they understand and in a place where they access information, the purpose of the research remains solely to serve the research community and those who write evidence based policy. Women will continue to access information interpreted by uninformed others and individualised care based on informed choice will be a dot not joined.

Dr Leslie Robinson, University of Salford

Dr Leslie Robinson, University of Salford

Call to action

Do you think there’s a role for professionals to get on-line to support patients struggling with the morass of health care information?

One thought on “Breast Screening Benefits and Risks: joining the dots”